Africans press wealthy nations on pollution at UN talks; Doubts emerge on a 2009 climate deal

By Arthur Max, APWednesday, November 4, 2009

UN climate talks focus on how to cut emissions

BARCELONA, Spain — African nations pushed wealthy countries at U.N. climate talks on Wednesday to explain how they intend to cut their greenhouse emissions under the landmark global warming agreement being negotiated.

Yet as delegates from 192 nations retreated behind closed doors in Spain, fears arose over just what will be accomplished this year on fighting climate change.

Sweden’s prime minister said achieving a legally binding pact was probably impossible this year, while the prime minister of Denmark said failure to reach a deal next month as planned would be “a massive disappointment.”

A flurry of diplomatic activity on a new climate deal reflected high tensions worldwide as two years of negotiations approach a climax at a major climate conference opening Dec. 7 in Copenhagen.

The conference had been due to anoint an agreement to regulate emissions of carbon and other greenhouse gases that cause global warming, but that deal seemed increasingly unlikely this year because the United States is not ready to commit to a specific reduction in emissions until Congress enacts a climate bill.

An emotional plea for action by German Chancellor Angela Merkel in an address before the U.S. Congress was met with silence Tuesday from most Republicans, while Democrats stood and applauded.

Republican senators also shunned the planned start of voting on amendments to a 959-page Democratic bill that would curb greenhouse gases from power plants and large industrial facilities. They protested that the bill’s cost to the economy — in the form of more expensive energy and the impact on jobs — had not been fully examined.

Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt, whose country holds the European Union presidency, lowered expectations further after meeting President Barack Obama in Washington.

Reinfeldt told Swedish Radio from Washington that “a legally binding agreement, like we have advocated in Europe, it’s simply not possible to deliver.”

The host of the Copenhagen conference, Danish Prime Minister Lars Loekke Rasmussen, said it will be difficult to regain momentum if the deadline is missed. He urged heads of government to step in to achieve a breakthrough.

“If we disappoint, it will be a massive disappointment, a setback where one will not be able to see how we can build that power again,” Loekke Rasmussen told reporters.

In Athens, the U.N. secretary-general said the talks had reached a “critical period” before the December summit, and warned that failure to conclude a pact — even an agreement of principles, than specific targets for cuts — would put the world’s most vulnerable in peril. Estimates vary on how many people have been displaced because of climate change, but the International Organization for Migration predicts 200 million people will be uprooted by environmental pressures by 2050. Some estimates, however, go as high as 700 million, according to a June report released at U.N. climate talks in Bonn.

Ban Ki-Moon said that, if climate change goes unchecked, the problem will only get worse. “Populations will relocate due to more extreme weather, including prolonged droughts, intensive storms and wildfires,” he said.

“In Africa, expanding desertification is … prompting more people to leave rural areas. So far these movements have occurred within countries. But that could very well change over time,” Ban said.

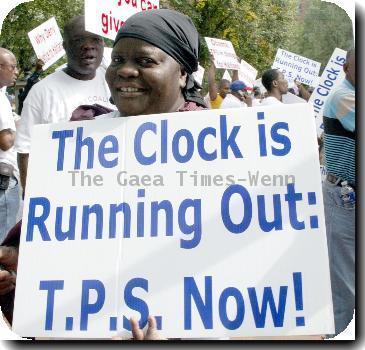

In Barcelona, a five-day conference preparing the text for Copenhagen resumed work after African delegates boycotted several meetings on Tuesday to press their demand that industrialized countries must raise their targets for cutting emissions.

Talks were held in small informal sessions from which reporters were barred.

EU delegates said the talks were back on track after a 24-hour disruption. As the Africans requested, industrial countries were spelling out how they intended to reach reduction targets in greenhouse gas emissions, whether by actual lowering domestic emissions or buying carbon credits on cap-and-trade markets.

Lumumba Di-Aping, the Sudanese delegate who heads a negotiating bloc of some 135 developing countries that includes the 50-nation African group, said the industrial countries had not responded to the Africans’ demand for new targets by the wealthy countries.

“I haven’t seen any real serious indication that they are upping their ambitions,” he said. “We will wait to see what happens.”

Emission pledges submitted by the industrial countries fall far short of the 25 to 40 percent reductions below 1990 levels that scientists say are needed to avert dangerous and irreversible climate change.

The developing countries demand that industrial countries reduce emissions by the full 40 percent over the next decade to blunt the effects of increasingly severe storms, floods and drought that already are causing havoc, especially in Africa.

The Copenhagen agreement is meant to succeed the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which required 37 industrial countries to cut emissions an average 5 percent by 2012. The United States rejected that deal because it made no demands on major developing countries.

Associated Press writers Jan M. Olsen in Copenhagen, Derek Gatapoulos in Athens, and Dina Cappiello and H. Josef Hebert in Washington contributed to this report.

Tags: Barack Obama, Barcelona, Climate-talks, Copenhagen, Denmark, Environmental Laws And Regulations, Europe, Events, Global Environmental Issues, Government Regulations, North America, Spain, Sweden, United Nations Climate Change Conference 2009, United States, Western Europe