Often overlooked, primary care doctors could hold the key to better quality, lower costs

By Ricardo Alonso-zaldivar, APWednesday, October 28, 2009

Could ‘medical homes’ bring order to health care?

A thousand miles from the health care debate in Washington, Dr. Don Klitgaard and his colleagues are carrying out their own reform in a small Iowa community.

They’ve reorganized their clinic so nurses bird-dog patients whose health problems, if ignored, could send them to the emergency room. And for all their patients, they’ve invested in a computer system that tracks leading indicators of health problems, like blood pressure and blood sugar readings.

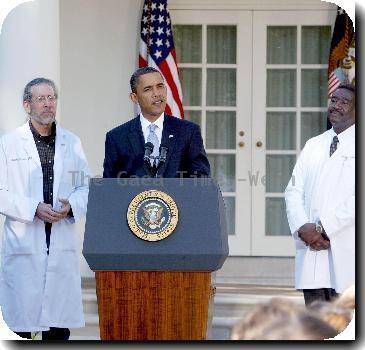

It’s not just country medicine for the 21st century. Policymakers from President Barack Obama on down have praised such experiments as key to getting better quality without costly complications.

But change doesn’t come easy. In a traditional practice, the doctor is the center of universe. In the new model, he or she is part of a team. Turning a doctor’s office into a “medical home” — what they call their model — starts with an attitude shift. Upfront resources and perseverance are also needed.

Klitgaard is wondering if Congress will do enough for primary care doctors, the ones expected to carry out the transformation. Medicare, the government health program for seniors, doesn’t pay for the care coordination, monitoring, and coaching of patients that are part of his model.

“We’re probably breaking even,” says Klitgaard, 41, of the Myrtue Medical Center in Harlan, Iowa. “Some patients who maybe wouldn’t have come in before are coming in. But if you threw the cost of electronic health records in there, we’ve probably lost money.”

Health care overhaul rhetoric, meet health care system reality.

To see why Klitgaard’s experiment is important, consider some basics from Health Care Economics 101:

—Three-fourths of Medicare’s budget goes to less than one-fourth of its clients, patients with five or more chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart failure or lung disease. They average 14 different doctors a year. Some juggle dozens of prescriptions.

Put primary care doctors like Klitgaard on the front end, the theory goes, and they could make sure patients see the right specialists, avoid duplicative tests, get proper medications and prevent the worst complications of chronic illness, such as diabetes-related blindness.

“Our system has gotten very good at paying for things to be done to patients, as opposed to keeping patients from having to have things done to them,” said Dr. Ted Epperly, chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

If primary care doctors are the lynchpin for success, that’s not what the system favors. Primary care physicians average $186,000 in pay a year as compared with $340,000 for specialists. So, no surprise that medical school graduates flock to the specialties, leaving the country with a worsening shortage in primary care. Canada has a 50-50 mix of primary care doctors and specialists. In the United States, primary care doctors make up just 30 percent.

Patients at the clinic seem happy with their care at the seven-doctor practice, which serves Harlan, population 5,400, and the broader area near the Nebraska border.

Kathleen Kloewer, 75, a self-reliant woman who worked the farm with her late husband and cared for seven children, says phone calls from the nurse keep her motivated to maintain her health. She has diabetes, high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol.

“We stay more on top of things, and I don’t let myself run way down before I go in on my own to see the doctor,” she said. “I used to find myself getting awful tired, and then I’d go in and find out I should have been there sooner.”

Paul Jensen, 69, retired from managing gas stations, has Type 1 diabetes and wears an insulin pump. He’s teamed up with a diabetes educator at the clinic who has the same condition and also wears a pump. She’s been able to adjust his pump so well that his blood sugar tests now approach readings that people without diabetes get.

“It keeps me out of the hospital,” said Jensen. Before the clinic offered diabetes education, he used to drive 135 miles to Ames every three months to see a specialist. Jensen is adamant: he’d sooner lose his doctors than his diabetes nurse.

“People are looking for healing and wellness,” Klitgaard said, “not just diagnosing or curing.”

Not only has the medical home approach improved patient satisfaction, there’s evidence it improves quality. In 2006, before the changes at the Harlan clinic, 55 percent of the patients with high blood pressure had levels below 140/90, considered fair control of the disease. By 2008, that had risen to 79 percent. Among the diabetes patients, 72 percent had moderately well controlled blood sugar levels at the outset. Two years later, it was 84 percent.

It’s too early to say if such gains will save the health care system money. The health care bills in Congress call for pilot programs to test the concept of medical homes, and quickly propagate it, if successful.

The legislation also aims to alleviate the shortage of primary care doctors. The Senate bill calls for changes in medical education so some federal money flows to community-based training centers that would turn out more primary care physicians. However, most federal money would keep going for specialist training.

Primary care doctors will also get a raise, with the Senate bill providing a 10 percent boost in Medicare fees.

Is it enough?

“Ten percent will help, but what you may really need is a 50 percent increase in Medicare payments,” said Fitzhugh Mullan, a George Washington University professor who studies the medical workforce.

Former Medicare administrator Mark McClellan, once a primary care doctor who served as Medicare administrator under President George W. Bush, gives the legislation a “B” or “B minus” overall on the issue.

“The steps are in the right direction,” said McClellan, “but I wouldn’t say it’s enormous leaps and bounds.”

Tags: Barack Obama, Diabetes, Diseases And Conditions, Family Medicine, Government Programs, Government-funded Health Insurance, Health Care Industry, Health care reform, Personal Finance, Personal Insurance, Personal Spending, Political Issues